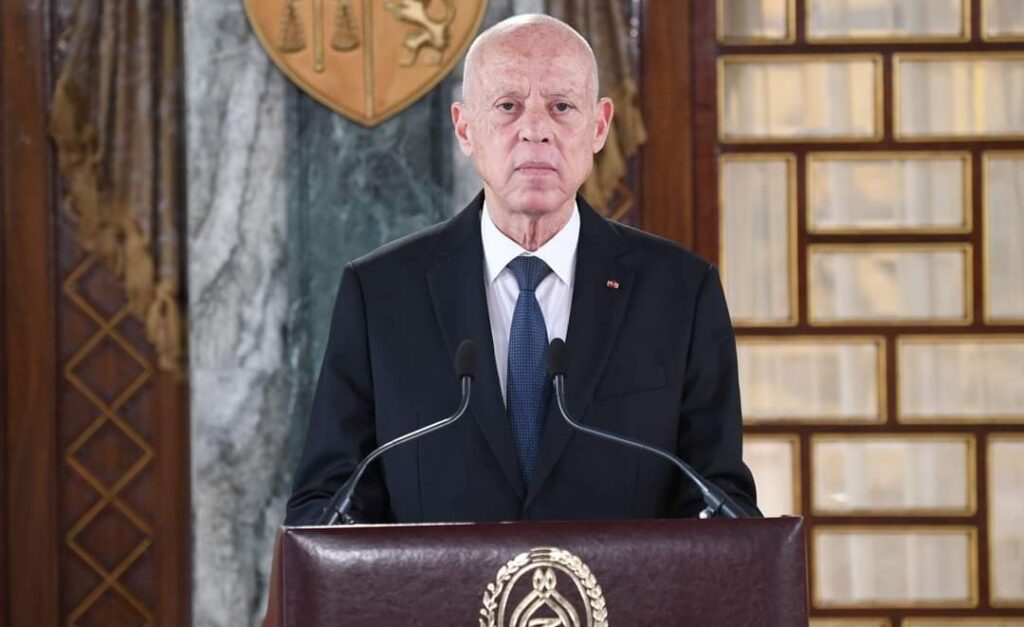

Tunisia was once a democratic, but it fell into the grip of a dictator. The recent massive trial of President Cais’ critics has been sentenced to up to 66 years of gruesome sentences, showing a new low in the ongoing authoritarian crackdown.

The trial provided an ock laugh of justice. About 40 people faced widespread accusations of “planning to destabilise Tunisia” and “membership of terrorist groups.” He fled from a country where more than half of the cases were tested by absenteeism, making it impossible for a fair trial. Independent observers were prohibited and defense attorneys prevented them from presenting evidence, but some defendants were deemed so dangerous that they were not allowed to attend court. Said had already been labelled as traitors and terrorists before the proceedings began.

Fake trials form part of a systematic campaign to challenge. Most opposition leaders now suffer in prisons. Critics faced arbitrary detention in harsh circumstances and often denied access to family, lawyers and medical care. Ahmed Soab, the defense counsel who dared to call the trial a farce, was detained shortly afterwards and detained with clear warnings to others who might speak up.

Said has also closed the doors for Tunisians who are seeking international justice. In March, his government rescinded a declaration that allowed individuals and civil society organisations to bring cases to African courts on the rights of humans and people. The body had previously ordered Tunisia to suspend Saeed’s decree, where he had plundered the judge and allowed detainees to access medical care, family members and lawyers. Even this limited measure of accountability will disappear once the withdrawal comes into effect next March.

Tunisia has fallen far away. After the 2011 revolution overthrew longtime dictators, the country seemed to be building a new democratic path. However, after winning the presidency in 2019, Saied dismantled the liberty that had been struggling with systematic. In July 2021, he rejected the Prime Minister, suspended Parliament and changed the constitution in 2022 to give him almost ambiguous power, including the rule of the Army and the judiciary.

The power grab was engraved rubber through a referendum with low turnout, and many opposition figures were subsequently jailed. Congressional elections in December 2022, held under a new voting system designed to undermine political parties, produced a compliant assembly filled with Said supporters. Said’s reelection for October 2024 was decided in advance, with only two other candidates allowed. One was sentenced to 12 years in prison before the vote.

Saied maintains some general support by ironically redirecting public frustration over economic failures towards black African immigrants. He repeatedly condemned them of the crime, claiming that they threatened their national identity. The outcome was disastrous. Immigrants have been rounded up, abandoned at the border, refugee camps are bulldozers, black Africans face increasing hostility and economic hardships. The organisations that once supported them have been criminalized and their leaders are detained.

Most troublesome, democracies have largely made Sayed’s abuse possible. As Saied strengthened his racist campaign in 2023, the European Union has signed contracts with him worth up to US$1.3 billion, including cooperation to prevent migration across the Mediterranean. The package included US$120 million, particularly to strengthen Tunisia’s border control capabilities.

The international community is finally showing signs of concern now. In January, the EU was forced to increase human rights scrutiny over partnership funds after revelation of gruesome violations by security forces against migrants. The UN Human Rights Chief criticized Tunisia’s pattern of arbitrary detention in February, and France and Germany recently raised concerns about unfair trials and excessive sentences.

Said dismisses these criticisms as expected as “blatant interference,” but democracies should not stop them. They should begin with the release of political prisoners and be conditional on a partnership that is conditional on respect for fundamental rights. The EU must ensure that financial support will only be provided if the government shows concrete progress in restoring human rights.

Last year, leaked documents revealed that EU officials are aware of the risks of credibility from partnerships with such prolific human rights violators. However, fundamental questions remain. How much must Said reveal himself as a dictator before the international community takes meaningful action?

*Editor-in-Chief Civicus, co-director and writer for Civicus Lens, and co-author of Civil Society Reports.

For interviews and more information, please contact lusears@civicus.org