Sarah Rainesford

BBC correspondent

BBC

Sonny Olumati was born in Italy, but still 39 and has no citizenship

Sonny Olumati was born in Rome and lived in Italy for his life, but the country he calls his hometown does not recognize him as its own.

For Italy, Sony is Nigerian like his passport, and the 39-year-old welcomes his latest residency permit.

“I was born here. I live here. I will die here,” the dancers and activists tell me what he calls “macaroni” under the palm trees in the sloppy Roman park.

“But not having citizenship is like being rejected by your country. And I don’t think this is something we should have.”

That’s why Sony and others are campaigning for a “yes” vote in the referendum on Sunday and Monday, suggesting that they cut the time needed to apply for Italian citizenship by half.

Reducing the wait between 10 and 5 years will make this country consistent with most other countries in Europe.

Giorgia Meloni, the solid Italian prime minister, announced that she would boycott the vote, declaring that the Citizenship Act was already “excellent” and “very open.”

Other parties allied to her are calling on Italians to go to the beach instead of the polling station.

Sony will not participate either. Without citizenship, he has no right to vote.

Insaf Dimassi says, “It’s extremely painful and frustrating to not be considered a citizen.”

The question of who will become Italian is sensitive.

Every year many migrants and refugees arrived in the country and were saved from North Africa across the Mediterranean by smuggling gangs.

The populist government in Meloni has helped a lot in reducing the number of arrivals.

However, the referendum is aimed at people who have legally travelled to work to countries with a rapidly shrinking and aging population.

The purpose is limited. Rather than making strict standards easier, it’s about speeding up the process of obtaining citizenship.

“The Italian knowledge of criminal charges, continuing settlements and more – all the different requirements remain the same,” explains Liberal Party Karla Taybi, one of several supporters of the referendum.

This reform will affect long-term foreign residents already employed in Italy. From people on factory production lines in the north to those looking after pensioners in the gorgeous Roman district.

Children under the age of 18 will also become naturalized.

Up to 1.4 million people can quickly qualify for citizenship, with some estimates high.

“These people live in Italy, study, work and contribute. This is to change their perception, and they are no longer strangers, but they are Italian,” claims Taibi.

Reforms also have practical implications.

As a non-Italian, Sony couldn’t apply for public sector jobs and even struggled to get a driver’s license.

When he was booked last year on hit reality TV show’s fame island, he was due to arrive two weeks late on the set in Honduras.

Reuters

Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni says she will appear at the polling station — but no votes will be held

For a long time, Meloni completely ignored the referendum.

Italian public media, run by close Meloni allies, pays little attention to the vote.

There is no substantial “no” campaign, making it difficult to have a balanced discussion.

But the real reason seems strategic. For a referendum to be valid, more than half of all voters must be known.

“They don’t want to raise awareness of the importance of referendums,” explains Professor Roberto Dalimonte of Lewis University in Rome. “That’s reasonable and to ensure we don’t reach the 50% threshold.”

The prime minister ultimately announced that he would appear at the polling station “to respect the ballot box,” but refused to vote.

“You also have the option to abstain when you disagree,” Meloni told the TV chat show this week after critics accusing her of rude democracy.

The Italian citizenship system is “good,” she argued that it already gives citizenship to more foreigners than most countries in Europe.

However, about 30,000 of these are Argentina, which has Italian ancestry on the other side of the world, and it is unlikely that they will even visit.

Meanwhile, Meloni’s coalition partner, far-right league Roberto Vannacci, has denounced the people behind the referendum “selling our citizenship and erasing our identity.”

I ask Sony why I think his own application for citizenship took over 20 years.

“It’s racism,” he replies immediately.

At one point, his files have been completely lost and he is now said that his case is “pending”.

“We have a minister talking about white hegemony – racial replacement in Italy,” the activist recalls a 2023 comment by the Minister of Agriculture from Meloni’s party.

“They don’t want black immigrants, and we know that. I was born here 39 years ago, so I know what I say.”

It is a charge that the Prime Minister repeatedly denied.

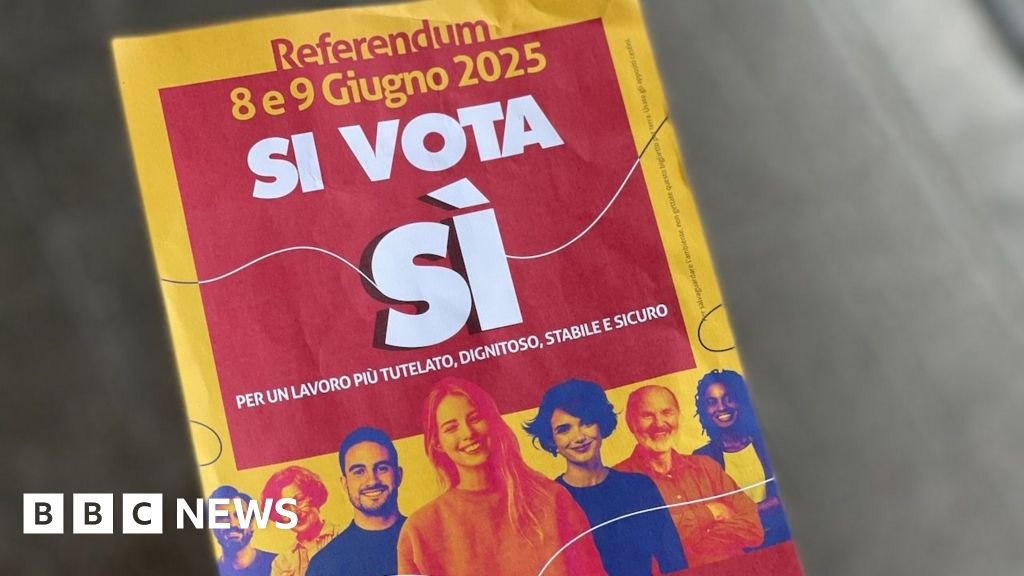

“Yes” leaflet for votes in Padua, Northern Italy”

Insaf Dimassi defines itself as “an Italian without citizenship.”

“It can be very painful and frustrating to not be considered a citizen because Italy has grown me and become the person I am today,” she explains from a city in northern Bologna where she holds her PhD.

Insaf’s father traveled to Italy for work when she was a baby, and she and her mother joined him. Her parents finally acquired Italian citizenship 20 days after Insaf turned 18. That meant she had to apply for herself from scratch, including proving a stable income.

Insaf chose to study instead.

“I arrived here at 9 months old, but maybe at 33 or 34. If everything goes well – I can finally become an Italian citizen,” she said.

She remembers the exact importance of “outsider” status when she hits her home. That was when I was asked to run for election with a candidate for mayor in my hometown.

When she shared the news with her excited parents, they had to remember that she was not Italian and not qualified.

“They say that what you have to get it is a matter of meritocracy that it is a citizen. But what do I need to demonstrate more than being myself?” Insaf wants to know.

“We are not allowed to vote or will not be represented, but we are not visible.”

On the eve of the referendum, Roman students wrote a call for a poll on the cobblestones of the city square.

Vote “Yes” on the 8th and 9th [of June]”They spelled them in giant cardboard letters.

With government boycotts and such modest publicity, the chances of hitting a 50% turnout look slim.

But Sony argues that the vote is just the beginning.

“Even if they vote for ‘no’, we’ll stay here and think about the next step,” he says. “We have to start talking about the location of our communities in this country.”

Additional Reports by Giulia Tommasi