Residents say Human Rights Day is almost meaningless in their town

Dozens of men were cutting grass on the road leading to George Tave Stadium in Sharpville, the venue for the official government’s human rights day, cleaning up trash that had not been recovered, and electricians were busy securing streetlights. People in Sharpville say this is the only time they’ve seen some kind of local government service.

“It’s the same story every year. They come a few weeks before Human Rights Day and do some cosmetic work as large politicians drive along these roads. Then they leave and we won’t see any service provided until next year.”

Hlongwane described the town’s condition as depressing. He believes the money the government is spending on the event will be spent more on improving the town.

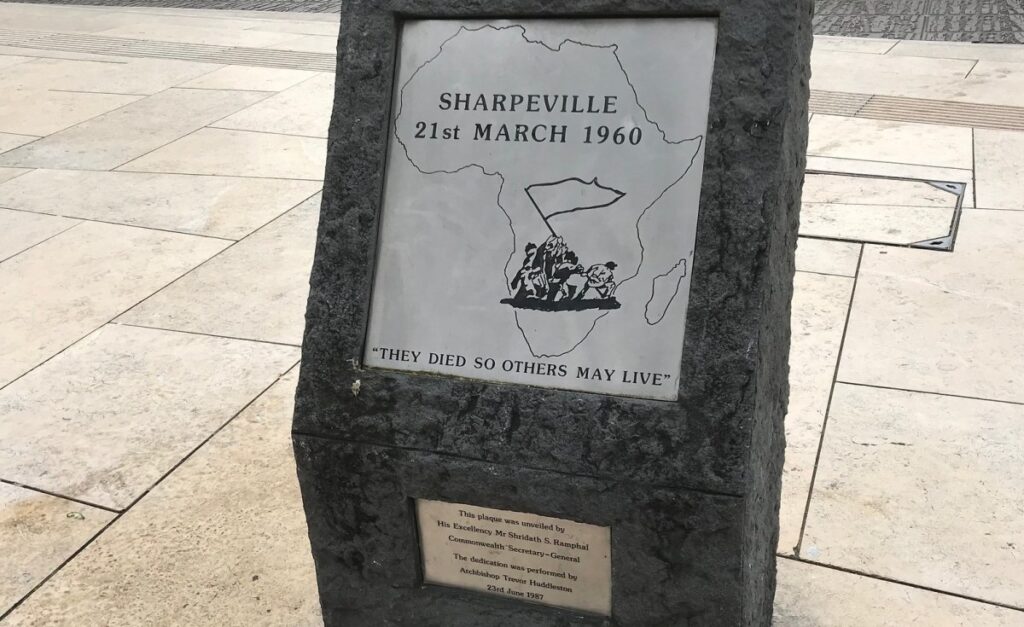

This year marks the 65th anniversary of the Sharpville Massacre on March 21, 1960, when at least 69 people protested against the Pass Act.

Located next to Vanderbihill Park, about 70 km south of Johannesburg, Sharpville is barely accessible due to its lack of stacking on street corners, open sewage and roads.

Sharpville is located under the local government of Emmafruni. Leading by ANC Mayor Sipho Radebe, it is one of the poorest performing municipalities in Gauteng, and has been placed under the administration several times.

Recently, Gauteng Mec of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs (Cogta) showed Jacob Mamabolo failed to spend R636 million in the city’s infrastructure grant. Emmafeni has been awarded R914 million in the last five fiscal years, but has spent only R278 million despite the collapse of infrastructure and services obstacles.

Sign up for the AllAfrica newsletter for free

Get the latest African news

success!

Almost finished…

You need to check your email address.

Follow the instructions in the email you sent to complete the process.

error!

There was a problem processing the submission. Please try again later.

In an interview with Africa in Newsroom, Mayor Siphoradebe accused his administration of emphasizing that he has no access to bank accounts after creditors like Eskom attached the account.

“Sharpville is a symbolic place in South African history. Our people’s blood flowed through these streets. Our constitution was signed here, but the people here do not recognize their constitutional rights. Isn’t it ironic?” resident Radebe told Groundup.

“Unemployment and crime are closely linked. There are levels of crime due to the rising unemployment rates. It’s very unsafe to walk around after the darkness,” Radebe said.

Mankamo Malikoe, 72, born and raised in Sharpeville, was seven years old at the time of the Sharpeville massacre. She still lives in a small shed, without basic amenities, in an informal settlement built in an old cemetery named Hlala Kwabafileyo (place of the dead).

She must walk to the main road, wearing a bright yellow church uniform, “taxi should not descend like this anymore,” she says.

Maricoe’s aunt Mamoto Shabi was among those massacred by the police. She was 21 years old and pregnant.

“I go to the cemetery and pay my respects to my aunt the day before human rights. That day, that cemetery is full of these politicians who create a luster. Create human rights. Human rights? What are human rights? I live here.