Mohammad Yousuf dar and his wife, Shameema, step into the front of the loom and skillfully tie the knot to create a pattern of the famous Kashmiri carpet flower, threatened by the Trump administration’s global tariffs.

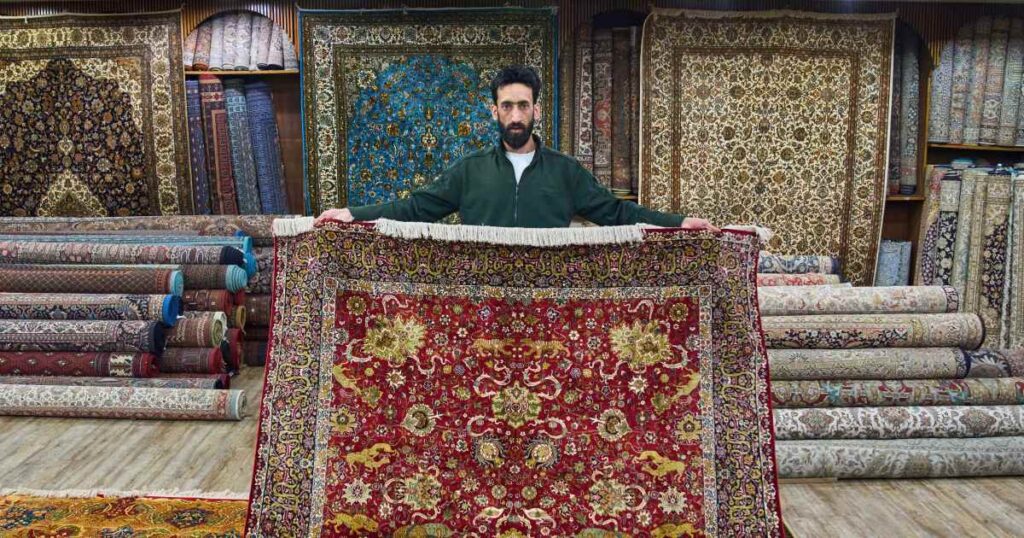

Surrounded by a real hand, Kashmiri carpets are usually made of pure silk and sometimes made of pure wool. Generations of artisans have passed crafts to ensure their survival for centuries, and carpets are expensive, but most artisans can barely interact with each other.

“I will help my husband and make sure I have a little bit of a reasonable income to run our home,” said Shamema, 43, who said she and Mohammad rhythmically picked them into colorful silk threads at a dimly lit workshop in Srinagar, a major Kashmir city where India was seduced.

They regularly look at a scrap of yellow paper known as Taleem or commands, and present patterns working with ancient shorthand notes of symbols and numbers and mysterious color maps.

Mohammad and Shameema studied craft at ages 9 and 10, respectively.

The industry has survived decades of conflict over conflict zones between India and Pakistan, endured the whims of fashion, maintained demand, and adorned mansions and museums.

But Kashmir traders say that US President Donald Trump’s import duties can take a major blow to already threatened businesses fighting for survival in mass-produced carpets.

Tariffs were primarily targeted at major exporters like China, but carelessly seducing the traditional handicraft industry from regions like Kashmir.

According to official data, carpet exports from India to the US alone are valued at around $1 billion out of about $1 billion.

Mohammad, 50, said he was the only weaver left out of more than 100 people who moved to other jobs in his neighborhood at an old centre in Srinagar city about 20 years ago.

“I’ve tied together months of rugs, but if there’s no demand, we feel our skills are worthless,” he said.

Still, thousands of families in Kashmir rely on this craft for their livelihoods, and the sudden 28% tariff imposed by the US means that imported carpets will become extremely expensive for American consumers and retailers.

“If these carpets become more expensive in America, does that mean that our wages will also rise?” asked Mohammad.

The chances are low.

An increase in costs to U.S. consumers often lead to higher wages for weavers, but rather lower orders for artisans, lower incomes and increased uncertainty, experts say.

This price hike could push buyers to cheaper, machine-made alternatives and rush Kashmiri artisans.

Insiders say that unless international trade policies change to protect traditional industries, they could continue to fray until Kashmir’s hand-work heritage disappears.

Kashmir carpet supplier Wilayat Ali said his trading partner, who exports carpets to the US, Germany and France, has already cancelled dozens of orders.

“The exporters also returned dozens of carpets,” he said. “It sums up in the tough arithmetic of profits and losses,” Ali explained. “They don’t have thousands of knots in the carpet that takes months.”